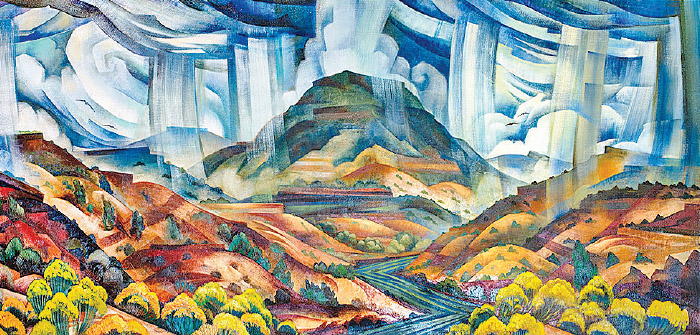

(Oil Painting by Tony Abeyta, Navajo)

A premise endures regarding Native American art that Indigenous Peoples had no real concept of the discipline until Westerners arrived. The argument goes, ‘prior to this, they would embellish items—utensils, tools, clothing—that served a utilitarian purpose.’ This position entails academic debate, however, and even then, no clear conclusion exists.

For example, an embellished Puebloan clay water vessel created 1000 years ago can be strikingly similar to an ‘artistically’ decorated pot made just last month by descendants at the same pueblo. The main difference between these pots is that the contemporary work will be sold as a work of art instead of being used as a jar.

Personal items of decorative adornment along with embellished implements were produced for millennia. The subtle shift to art items per se occurred in the late 1800’s due to the economic opportunities these works began offering for people who had exceptionally few income possibilities.

Western Society did not teach Native Americans ‘the what or how’ of art making but did influence them with regard to ‘the appearance’ of certain products for the purpose of enhancing ‘the value’ of their traditional efforts.

Traditional hand-loomed Navajo blankets illustrate this shift. Made in the 1700 and 1800’s before the United States conquest of the Southwest, these blankets were something that the Navajo could potentially produce and then trade for necessary goods once the reservation era began. Yet, making these blankets was too time consuming to allow successfully competing against the mass-produced, low cost textiles of that era.

Trading Post agents on the Navajo Reservation understood this and encouraged a subtle design shift. With fairly minor changes, the blanket weavings became rugs; conceptual guidelines for new patterns were also introduced. This resulted in the iconic Navajo rug, which has become a showpiece in countless well-heeled, Western ranch style homes over the past 125 years.

Native American jewelry demonstrates another medium that underwent a transformation during the late 1800’s. Personal adornment or ‘jewelry’ products have been found in North America dating to Pleistocene times. However, the famous silver and turquoise jewelry of the Southwest commenced in the late 1800’s.

Silversmithing, initially learned from the Spanish by a few individuals, quickly developed within a contingent of Zuni, Navajo and Hopi men. They explored and developed processing methods in stone settings and stylized a unique type of jewelry that is now thought of as ‘theirs.’

Mainstream society’s knowledge and desire for so-called primitive artwork and jewelry commenced in the early 1900’s. Demand steadily grew, exploded in the late 1970’s, its zenith of popularity lasting until the mid 1990’s. Multiple artist shows commenced during the 20th Century, and the best of these are juried, single weekend events. The annual Santa Fe Indian Market, occurring each third weekend of August, brings together 800 artists, and 100,000 visitors while providing a $200 million influx for the New Mexico town.

Art and jewelry making holds a disproportionally important economic position for Native Americans tribes due to the exceptionally high unemployment rates on the reservations. The financial impact that a highly successful artist or jeweler can have for one family might be sufficient to provide them with the highest standard of living in some reservation communities.

The town of Zuni on the Zuni Reservation in New Mexico is believed to have the highest number of artists per capita for any community in the United States. It is the same with the First Nations Inuit town of Cape Dorset on Baffin Island—they have more artists per capita than anywhere in Canada. The financial importance of art in some locations such as these can make or break the town’s welfare.

The artwork of Native Americans often reflects their traditional relationship with the local surroundings, which manifests as being extensive and spiritual—the earth, materials and life. This perspective infuses an innate, intuitive understanding and connection. Whereas creating a work based solely upon an artist’s inspiration or ‘inner muse,’ without regard to cultural traditions or local surroundings, would be what Westerners refer to as ‘art for art sake’ and seldom occurs.

The most traditional appearing works made today—Northwest Coast masks made of cedar, Hopi Kachina dolls of cottonwood tree roots, Pueblo pottery of the local earth—honor these Peoples ways of belief and craftsmanship as they have been practiced for centuries. Artists often state that these particular works are made after a blessing, with prayers intended for the world.

Borrowing or appropriating tools and ideas from other cultures has been practiced among humans throughout time. Native Americans are no different, to include the realm of art. For instance, a small number of Native American artists now utilize the Pop Art approach, digitizing images from their culture.

With regard to contemporary works, their ‘modern’ appearance can construe an incorrect perception about its ‘Native-ness.’ An example would be paintings that are oil-on-canvas, which give the impression of a European genre. Yet paintings have a distinctive artistic lineage for North American Tribes—

People painted on rock walls for millenniums across North America, leaving behind tens of thousands of still existing pictographs. At some point, early Native Americans also began painting on animals skins, sometimes using these as an annual ‘winter count’ to mark the passing of years. After Westerners conquered these lands, killed off the buffalo and sent the People onto reservations or to prisons, the materials necessary for the skin

paintings disappeared.

The first reservation Indian agents of the Great Plains or the officials at prisons where warriors were sent began giving these former painters and indigenous historians the used pages from their ledger books, along with fountain pens, crayons, or watercolor paints. This period of ‘ledger art’ continued into the 1910’s.

In the 1920’s a group of Southern Plains Indians in Oklahoma, The Kiowa Five, began an art movement with more contemporary art supplies. They initially based their style of work on the ledger art genre, and it came to be known as The Plains Style. The Studio School opened within the Santa Fe Indian School in 1932 and further developed the ledger art approach with contemporary materials into what is now regarded as the Santa Fe Style of Native American painting.

From this era of works, the genre of Native American painting moved down other paths to include commonly using oils on canvas by the 1960’s. Thus, while oil-on-canvas works are not a traditional American Indian art form, painting most certainly is, and it carries a distinct lineage.

Multiple challenges face Native American artists today—non-Natives offering Native American ‘theme’ works that typically depict a romanticized perspective of American Indians of the 1800’s; the current pricing levels of raw materials; the loss of art instruction in elementary and middle schools due to shifts in educational funding; the Far East imitation/ counterfeit trade, which grows each year; and competition with the older Native American artworks of 50 to 100 years ago via estate sales and auctions. However, what’s recently developed as the biggest threat, and will be the topic of the final column in this series, is the impact of cyber technology and social media upon what should be the next generation of artists.