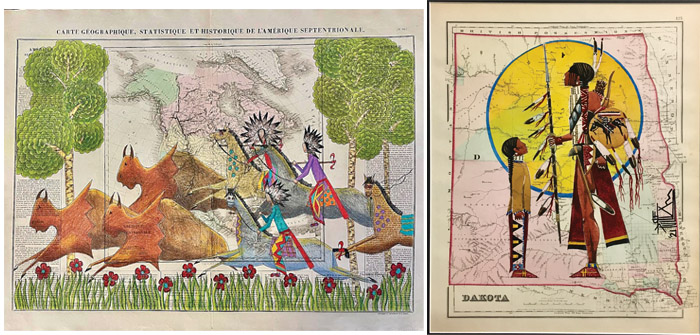

((L) Buffalo Hunt by Dolores Purdy, Caddo-Winnebago, on Buchon’s 1825 map of North America, 19” x 25”, (R) I want to be like you when I grow up father., by Joe Pulliam, Oglala Lakota, on Gray’s 1873 map of Dakota Territory, 12” x 15”)

Raven Makes Gallery in Sisters is offering the second edition of The Homelands Collection, which began on May 13. The collection consists of 65 antique original maps from the 17 and 1800’s with artwork drawn upon them by 20 Native American artists. These are new works that were commissioned by the gallery for the collection.

There is a map of North America from the 1830’s that labels a region in Northwest Canada as being occupied by the “Quarrelsome Indians,” an area of the Upper Plains by “Rat Indians,” the Rockies by “Wolf Indians” and an area of the Great Basin by “Sand Digger Indians.”

A 240 year old map locates only two tribes, the Sioux, shown in the Upper Plains, and the Apaches, who were somehow placed in southern British Columbia. Another map, from the early 1840’s, details the proposed relocation of the Eastern tribes to tracts of land on the western banks of the Missouri River, identifying one small reserve as “Half Breeds Town.”

A number of antique maps correctly identify Indigenous Peoples by English names that are still in use today and show them at their correct locations. These cartographers and publishers were possibly motivated to do so out of ethical considerations. It is more likely, however, they comprehended that the lucrative atlas market of the era would be best served with the most accurate maps possible.

Maps of long ago provided a vital secondary purpose for European nations. In addition to geographic knowledge, maps were used as legal instruments.

Along with a planted flag and a proclamation-deed, maps offered legal evidence for European laws rationalizing their occupation of foreign lands. Thus, they usurped lands from Peoples who had inhabited them since time immemorial with one justification being that Indigenous Peoples failed to ‘record’ the boundaries of their lands.

Establishing dominion often required self-righteousness. Some maps showed California as an island or called the Western Hemisphere ‘Atlantis’ or displayed a vast inland sea that covered much of the American West. No matter, even woefully inaccurate maps were given precedence over the inhabitants who correctly understood the geographic terrain.

Today, Indigenous Peoples seek redemption for historic injustices, but redemption comes dropping slowly when your people were conquered and ordered to assimilate, with survivors cast to the margins. Yet glean measures of redemption they shall with one longstanding venue for their traditional cultures being the art world.

Within the second edition of The Homelands Collection, examples of cultural continuance, affirmation, and acknowledgement of tragedies include—

Sitting Bull’s Vision of Soldiers Falling Into Camp by George Levi Curtis, Cheyenne and Arapaho, demonstrates the storied dream of the great leader and holy man just a few days before The Battle of the Little Bighorn. Custer himself appears on this 1876 celestial map.

On Chasing Away Buffalo by Dallin Maybee, Arapaho and Seneca, an Iron Horse is depicted, scattering the buffalo before it, on an 1889 Railroad map of the United States.

qangiquusinaq (long long ago) by Heather Johnston, Alutiiq, shows her people in baidarkas (kayaks) hunting wiinarpak (walrus) from 6,000 years ago on an 1827 map of the Southcentral Alaska Coast.

The Homelands Collection will run from May 13 to June 13. Any maps acquired during this time will be released after the exhibition concludes. Heather Johnston will attend the private, collectors only showing on May 12.